Task Force on Resources

Final Report - April 2, 2008

-

The Current State of the University

-

Introduction

The University of Toronto’s stated mission is “to be a world class, publicly supported research and teaching university”.

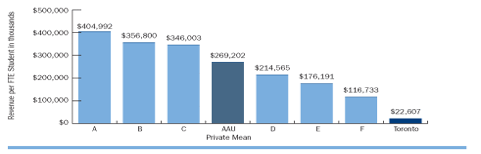

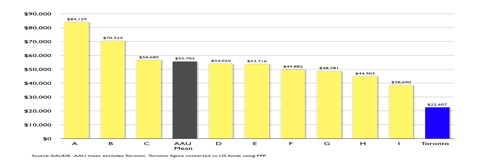

We have for decades managed to do a remarkable job in fulfilling this mission, despite the fact that our resource base is paltry compared to that of our competitors. We are ranked among the world’s best public universities. We have a notably strong record of scholarship and of educating generations of leaders through demanding undergraduate programs and a wide array of renowned graduate and professional programs. Figures 1 and 2 provide stark evidence of how little revenue the University of Toronto receives per student when compared to AAU peers.

Figure 1 - The Widening Gap in Per-Student Funding - Private

2005-2006 in US$ (Select AAU private peers)

Figure 2 - The Widening Gap in Per-Student Funding - Public

2005-2006 in US$ (Select AAU public peers)

We have also managed to maintain strong financial controls and contain our expenses within our revenues. But we are at the breaking point. The current resource situation of the University of Toronto can only be described as unsustainable. Unless things change we will find both the quality of our teaching and the quality of our scholarship eroded, as the student-faculty ratio climbs, buildings crumble, and our best faculty leave for greener pastures.

-

The continued pressure to grow and add students

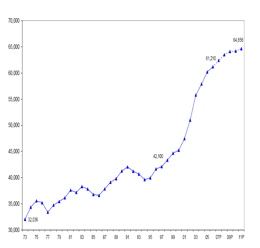

Figure 3 - FTE Enrolment at the University of Toronto

Figure 3 - FTE Enrolment at the University of Toronto

1973-74 – 2012-13Since 2002, the number of undergraduate full time equivalent (FTE) students has increased from 51,702 to 63,073, an increase of nearly 22%. In 1997, enrolment was only 42,100 FTEs. The reasons for the high growth levels are clear – demand for post-secondary spaces in the GTA continues to escalate and government funding is often, if not always, tied to increased numbers. We have increased our student population to generate more revenues.

As the undergraduate demand increases, so does the demand for graduate places, as these new students move through their educational careers. The U of T has increased graduate enrolment from 10,782 in 2004 to 12,473 in 2007, providing a great proportion of graduate education across the province, as is only to be expected of a research-intensive university.

-

The restrictions on revenues

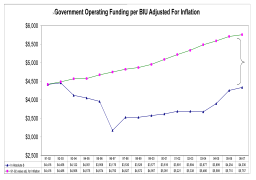

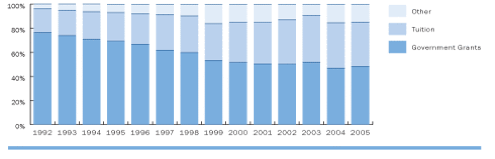

Increased demand is, of course, a good thing for our province and our country. Unfortunately, we are struggling to meet that demand, as the funding for students has declined over the past decades. We are receiving less per student today than in 1992. (Figure 4). Ontario universities receive less than the national average per student from the government. (Figure 5)

Figure 4

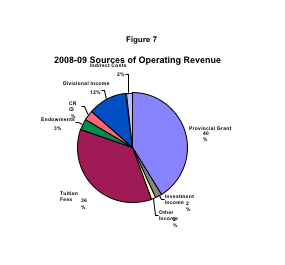

In 2006-07, U of T’s operating budget was about $1.2 billion. The core provincial grant currently represents about 48% of that total, down from 76% in 1991-92. Tuition has risen from 20% to 37% of revenue. The remainder comes from other sources, such as endowment payouts, federal government support and divisionally generated income. (Figure 8)

This shift has occurred because the government controls two of the key revenue lines. Government grants per student (BIU’s) have not increased enough to cover inflation and are based on formulas developed in the 1970’s, which no longer reflect the cost structures of the programs they are intended to fund.

The government also controls tuition rates. Even where students have demonstrated a willingness to pay a higher tuition, the government prefers to hold tuition rates down.

Over the years, structural deficits have been built into the system. Tying revenue increases to increases in volume means that these deficits continue to increase, as our resources are used to solve problems created in the past, not to improve the quality of education for our current students.

Research funding is another area of concern. At the present time, only 16% of the indirect costs associated with research are covered by research sponsoring agencies. If this amount were increased to 40%, the immediate impact would be an increase of $60M.

Figure 5 - Government Funding Gap: Canada

To reduce dependence on government funding, the University of Toronto has turned to our community with great success, resulting in a significant expansion of our endowment. Unfortunately, this too is a double edged sword. People and governments tend to see us as wealthy and do not understand that only the earnings on the endowment are expendable. We must carefully balance the level of the payout to provide stability in funding, protect against inflation, and maintain a reserve to permit payouts even in years when investment returns are negative. In addition, the desire to limit risk constrains the return that can be achieved on investments. It is a challenge to communicate the perpetual nature of endowments as well as the investment and payout strategies to a population that is interested in achieving the highest returns.

Donors have also been generous in providing funding for capital projects and to support faculty programs and new initiatives. Unfortunately, no donors seem interested in funding maintenance and repairs, or basic infrastructure like plumbing and steam plants.

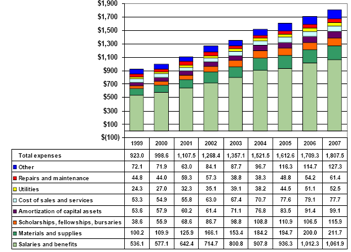

Figure 6

Expenses by Category for the year ended April 30, 2007

(Millions of dollars)

Costs are increasing at a faster rate than revenues

Each year, the University of Toronto prepares a budget for approval by the Governing Council. Each year, this budget is either a balanced budget, or if there is a deficit, there is an identified plan to eliminate that deficit within a specified period of time. Each year, faculties and divisions initially receive more money than they had the year before, but cuts nonetheless have to be made to service levels, to programs or to staffing. Why does this happen?

The cost structure of the university is dominated by the cost of people. Salaries and benefits account for about 70% of the operating budget. Given that wage and benefit increases are driven by a variety of factors including international competition for top faculty, union negotiations and general market conditions for wage increases, the cost of people has increased annually at rates significantly higher than the general level of inflation. This situation is compounded by a desire for pension and benefit improvements without increased contributions by members, by imposed settlements with the Faculty Association that take no account of the ability of the University to pay for the increased costs and by accounting changes that will require the addition of unfunded future benefits liabilities to the balance sheet.

Human resources are not the only source of rising costs. Utilities costs have been rising at rates higher than inflation and are expected to continue to do so. We have extensive energy saving and demand management programs underway, but costs will continue to rise.

Years of not investing in the physical infrastructure have created another set of problems, as a large backlog of deferred maintenance must be managed. The challenges of managing the physical infrastructure include a large number of heritage buildings, the legislative requirements for improved access for disabled persons and the challenge of renovating spaces to meet the requirements of today’s technology enhanced teaching.

-

Increased debt levels

During the years when enrolment growth was modest, universities had very limited capital spending programs, as our teaching and research could generally be accommodated in existing facilities. Where a new building was required, government support for the project was often available. Over the last years of high enrolment growth, the situation has changed dramatically. Government funding has been reduced and the University of Toronto has used debt to finance a billion dollar capital program. Debt on our balance sheet has increased by a factor of ten since 2000. Interest and other debt service costs require about $30 million from the operating budget.

In addition, the government’s desire to keep debt off their balance sheet has resulted in transferring it to ours. For example, the graduate expansion program is funded by a stream of payments sufficient to cover debt service costs, assuming that we borrow to be able to take on increased numbers of graduate students. This allows the government to spread their costs over a long period rather than providing upfront funding.

-

Governments desire to treat all universities in Ontario identically

The provincial government has a tendency to treat all universities as a homogenous group and fund all on the same basis. This ignores the vast differences between universities - their different programs; different cost structures; different student groups with different needs; and different goals. If there were a clear vision for post-secondary education across the province, priorities could be established and money invested strategically. Ontario could have a range of universities to meet a range of needs, from the small university focused on serving the local population, to the large research intensive university serving a national and international population, as well as driving the Ontario agenda for innovation and quality.

-

Conclusion

The conclusion is obvious – something has to change. The next two sections will discuss some of the options considered by the task force.

-

-

Working Towards a Better World

The Task Force discussed a number of routes we could take towards an improved situation, beginning with an examination of where revenues come from and concluding with a review of how they are spent.

-

Strategies to Increase Revenues

There are only four main sources of university funding: government grants, tuition, corporate partners and gifts. Selling assets would of course be another possible source of revenue, but that would be short-sighted and not sustainable in the long run. Figure 7 presents the major sources of revenue by category.

-

Government

Government grants account for the largest single source of revenue. Most of these grants are allocated on the basis of the number of students, multiplied by a predefined unit rate (the BIU) that was established on the basis of a 1970’s cost analysis. The University of Toronto, along with the other Ontario universities, has lobbied unsuccessfully for increases to the basic rates. We have also lobbied, along with some of the other Ontario universities, for differential allocations across universities. These attempts have not been successful. We have not even managed to get inflationary increases.

We are thus in a position in which the vision for post-secondary education in Ontario is in dire need of clarification. Our part in this process must be to communicate and promote the value of having a small number of major research universities in this province and this country so we can forge a common cause with others with similar ambitions.

We must continue with our efforts to both increase the provincial government’s share of the cost of a university education and to argue for differentiation between universities. The Government of Ontario needs to promote all kinds of post-secondary education in this province, making strategic investments in education instead of spreading funding evenly. Only then will we have a system of post-secondary education that is of maximum benefit to the wonderful myriad of students we have in this province. And only then will we maintain our research engines, which are major drivers of the economy.

A third strategy follows on the heels of the differentiation idea. Government funding of the full costs of research has long been a lobbying issue and must continue to be so. The key question is: does the Government want leading edge, research intensive universities? If the answer is yes, funding strategies must change.

Figure 8 - University of Toronto Operating Revenue 1991-92 to 2005-06

-

Tuition

Another strategy that we must look to is tuition flexibility. Although we cannot envision a context in which we would not remain dependent on government as an important source of funding for operating costs, we can envision continuing to increase the importance of tuition. This, of course, would come with our confirmed commitment to guaranteeing access, through various forms of student aid - grants, loans, scholarships, back-end debt relief, etc. This commitment is something that we have upheld with great rigor across all of our programs, including those with higher tuition fees.

The Task Force thus recommends that we continue to advocate for responsible self-regulation of tuition. On this model, the University would be responsible for establishing the appropriate tuition level for each of its programs, reflecting more accurately actual operating costs, quality of the experience, and demand.

Included in the concept of self-regulation is an elimination of the restrictions on ancillary fees. A number of Canadian universities have already demonstrated that students are willing to pay such fees to enhance the quality of their programs. A clear and self-regulated ancillary fee policy allows for justifiable costs to be charged to the student in a transparent and flexible manner. Program-specific ancillary fees also ensure that the students who benefit from the program are the ones who contribute, avoiding the inequities of cross subsidization.

The Task Force also deliberated about changing the way we think about tuition. Some faculties have already shifted to a program fee instead of a per course fee, which allows a higher value to be placed on the program as a whole instead of charging an identical fee for each individual course. A program fee structure provides the opportunity to differentiate programs based on cost of delivery and overall value to the students. Moving all faculties at the University to the program fee mechanism would improve consistency in practice and best rationalize our resources. In some cases it would provide a modest discount in overall costs to those students who take course loads above the usual full load of five full credit equivalents.

The Task Force also considered a wide range of options related to students. One is to change the mix of students (domestic undergraduate, international undergraduate, doctoral stream, professional masters, etc.). Clearly, this would involve questions about the very character of the University of Toronto and these questions will be considered by the Task Force on Enrolment, as will the question of what is the appropriate total number of students for our university.

Another option involves the graduate student guarantee and the restructuring of doctoral stream funding. Currently doctoral stream students are guaranteed funding for up to five years of study. In Arts and Science, for example, the minimum level of support varies from department to department and is between $13,000 and $19,000 (plus tuition and fees). While most research universities support graduate students, the University of Toronto is unique in its blanket guarantee. We have not always been able to be competitive with our peers using this model of graduate student funding and there is strong feeling that we need to rethink our approach to it. We need more flexibility and more strategic allocations of funding than can be provided under the current broad-brush policy.

-

Partners

The University has formed some excellent and valuable partnerships with private enterprise in the past. So long as academic freedom is in no way compromised and genuine advantages can be demonstrated in quality or efficiency, the Task Force recommends the expansion of such partnerships in the future. We suspect that partnerships for construction and operation of buildings, implementation of technology and management of ancillary operations, etc. could be fruitful ventures. In the academic sphere and again provided academic freedom is meticulously safeguarded, the university could perhaps create more specialty programs with industry partners. Students would benefit from having contact and discussions with individuals in their field and the University’s net revenues for such programs could be higher than is usual.

-

Friends and Benefactors

The Task Force spent a great deal of time discussing issues regarding gifts and the endowment. Compared to our Canadian peers, we have a very large endowment, but compared to our US peers it is small. The Task Force recommends substantially increasing fundraising efforts. Indeed, doubling or tripling the current endowment would be a highly desirable result.

Most gifts to the University currently go into the endowment fund, which makes an annual payment to support a designated purpose. If we were to have a real and immediate impact on the operating budget, we would need to change our campaign strategy to include annual gifts and expendable donations. This would be a more volatile revenue stream, but the Task Force felt that our track record of successful fundraising might permit this to be considered as we go forward. Some committee members strongly supported the idea that we should raise the endowment pay-out as a means to increase funding for operations, but that needs to be considered in the light of our current commitment to preserve capital.

-

Existing Assets

The Task Force also considered how the University might leverage the value of existing assets, by taking action to minimize the negative financial impact of carrying assets that are not used for academic purposes and selling assets for which there is no long term requirement anticipated. We discussed selling the University of Toronto Press, selling all off-campus residences and other residential properties, and re-thinking the first year housing guarantee.

Clearly there are many substantive curricular and academic questions that need to be answered before any decisions to sell assets could be made. These questions are well beyond the scope and the expertise of the Task Force on Resources.

-

Strategies to Increase Productivity

Though the focus of the Task Force is on increasing revenues, it is clear that finding efficiencies in the current operation of the University would also add to the bottom line. One recommendation of the Task Force in this regard is that the University centralize non-academic processes and manage them with a view to reducing costs. For this to work, the centralization would have to receive real buy-in across the University – ideally, use of centralized processes should be made mandatory. Some options for centralization include increasing purchasing through the procurement office and centralizing management of information technology with uniform standards, policies and purchasing.

Another option is to maximize the use of resources. For example, though some room bookings are controlled centrally, the University could move to have all room booking controlled centrally and be available through a computer booking system. Classes could be offered in different time slots in order to maximize the use of the building space on weekends, evenings and through the summer.

We also need to look at the administrative work done at the University to see if there are more efficient ways to deliver services at lower costs. To make the academy more productive, the current workload of faculty could be reviewed in an effort to maximize time spent on the core mission of research and teaching. There may be a need to hire more professional staff to take on administrative roles rather than requiring faculty to spend time doing tasks that can be done by others. This may mean that faculty members spend more time with students and less time participating in committees, that we revise our policies related to buy-outs from teaching, or that we continue to assess how technology can be used to improve efficiency. Faculties are already examining whether they have the appropriate mix of teaching-stream, tenure-stream, shorter-term contract, and status-only faculty to properly meet the needs of their students. This again requires that important questions about the character of the University be answered.

Finally, the University also needs to assess its programs, departments, and faculties on a regular basis to determine whether they are competing on an international level, whether other institutions in Ontario or the Toronto region are covering the same ground effectively, and whether these academic initiatives are essential to the core mission of the University. If they are not, and if they do not generate sufficient revenues to cover their costs, consideration should be given to discontinuing them.

-

Strategies to Reduce Costs

Like many public sector organizations, there are few places in the University where simple cost-cutting remains a viable solution to funding issues. Our revenues, and by definition our expenditures, are low and our outputs – both in terms of the quality of student we graduate and our research output– are enviably high.

Salary and benefits make up one billion dollars of the 1.8 billion dollar total expenditures and more than 70% of the operating budget. Cutting numbers of faculty or staff, or not hiring to replace those who leave, has been the traditional method of achieving budget constraints. The result of these cuts has been an increase in the student-faculty ratio, a decline in quality of the student experience, a delay in turn-around times on critical projects and an increase in risk across the University when work is either not done or is not completed in a timely fashion.

Though salaries and wages are market driven, the current annual raises across the board may need to be revisited. If the current wage increases are continued over the next few decades, it will be harder for the University to raise the necessary funds to support them. Any revision we make to our practices here will clearly have to take into account the need to hire and retain only the best.

The costs of our benefits programs are of increasing concern, particularly since accounting regulation changes will require us to show unfunded liabilities for future benefits on the balance sheet, which will have a negative impact on our net asset base and reduce our ability to borrow. Changes to benefits plans are extremely sensitive, and cannot undercut obligations to current employees that are contractually and morally grounded. However, in contracts for future employees, the question will become whether we can offer exactly the same benefits as have been enjoyed by current employees.

-

-

The University of Toronto in 2030 – Possible Worlds

The University of Toronto will continue to be an excellent university in 2030 with leading faculty and top students doing work in an environment that is conducive to research, teaching and a high quality student experience.

This goal underpins our analysis of scenarios that are possibilities for the University of Toronto in 2030. Some of these possibilities are far-fetched and highly undesirable. We include them for instructional and comparative purposes.

We also assume that the administration and governors will continue to demonstrate their commitment to prudent financial management by controlling deficits and ensuring that we do not get into a position of financial imbalance that would risk either our reputation or our ability to deliver on our mission.

Given the complexity of the University and the 2030 horizon, we have focused our analysis on the key variables, spoken to above, that might have a significant impact on the financial picture of the University: enrolment levels and changes in enrolment mix; the value of the government grant; tuition rates; the size of the endowment; the payout level on the endowment; increases in salaries and benefits; the cost of research, etc.

Other variables – those having to do with changing from course to program fees; charging higher rates for out-of-province and out-of-country students; increasing ancillary fees, etc. – do not have a significant impact on the financial situation and hence do not figure in the scenarios that follow. Nonetheless these proposals should be considered in more detail as part of a continued program to increase revenues and decrease costs.

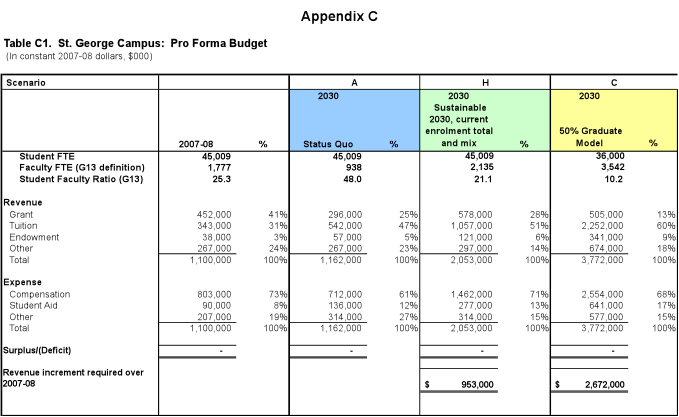

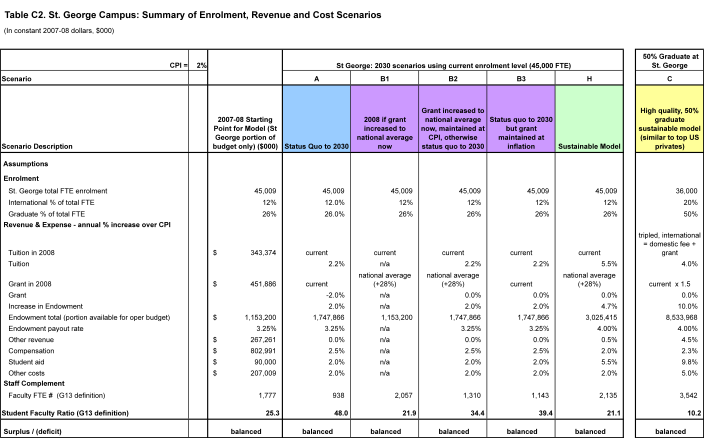

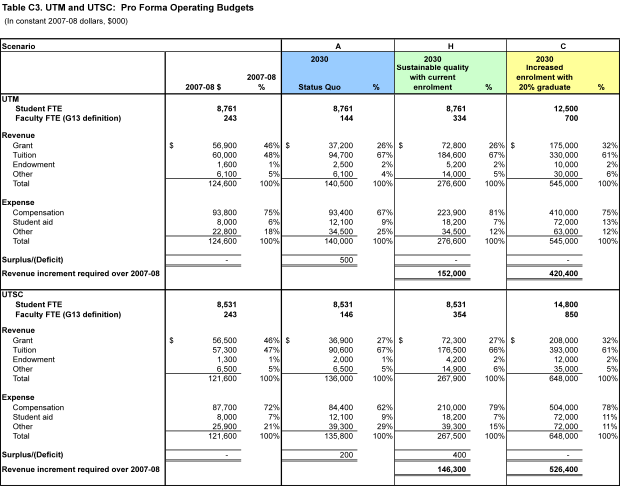

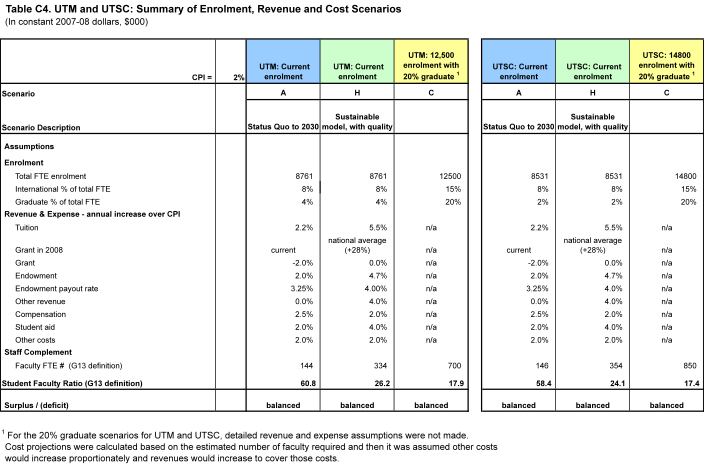

The data underpinning the scenarios are attached as Appendix C. It is important to note that student-faculty ratios (using the G13 methodology) are used as an indicator of quality although it is recognized that student-faculty ratio, class size, and quality of the educational experience are not always positively correlated. Some courses lend themselves to high quality in a large class environment and some do not.

The projected revenues and costs given in Appendix C have been derived from a simplified financial model that enables various scenarios to be explored. Table C1 gives the projected revenues and costs for the St. George campus for some of the scenarios described below. Table C2 gives a summary of the assumptions, an estimated faculty count and the resulting student-to-faculty ratios. Similar data for UTM and UTSC are given in Tables C3 and C4.

All the projections in Appendix C are expressed in constant 2007-08 dollars and assume inflation to be at 2%. For example, in the past two years, tuition fee levels have increased at an average rate of 4.2% per year across the University. Scenarios in which tuition levels are assumed to continue to increase in the same manner use a rate of 2.2% above inflation.

Scenario A: The Status Quo

Here we assume that we continue along the track we are currently on – the grant does not increase with inflation; tuition rates remain constrained as they are at present with an average increase of 2.2% above inflation; inflation continues at 2%, salary and benefits costs increase at 2.5% above inflation, and the size of the endowment increases at 2% above the inflation rate. In this case, by 2030, to achieve a balanced budget we will have to reduce the number of faculty and staff by more than one third and increase the student-faculty ratio from the current level of 25.3 to 48.0 at St George. The situation is even more extreme at UTM and UTSC, where the student-faculty ratios will increase to 60.8 and 58.4, respectively. Quality will be significantly impaired.

Scenario B The Grant Model

In this scenario we consider a variety of changes that might be made to the grant. If the grant we receive today were at the national average level, an increase of 28%, we would be able to have an

additional 280 faculty at St. George and a student faculty ratio of 21.9, with a significantly improved student experience.However, even if this higher level of grant were subsequently increased at the level of inflation, by 2030 the student faculty ratio would climb again to 34.4; so it is clear that changes to the granting formula are not by themselves sufficient to solve our problem. If the current level of the grant were increased with inflation, the situation is better than the status quo, but the student faculty ratio reaches 39.4 by 2030 —still not a desirable future. Similar results can be seen in Tables C3 and C4 for UTM and UTSC.

Scenario C: The Enrolment Model

In this model, we examine the possibility of increasing graduate enrolment to 50% of the student population at St George, and 20% at UTM and UTSC. To do this and provide a high quality experience, similar to top US private universities, we would need to triple the domestic tuition level and increase it at 4% above inflation annually. The size of the grant would have to increase by 50% and keep pace with inflation. And the endowment would have to quadruple to $8.5 billion. This may be a desirable future, but it is not considered realistic. The Enrolment Task Force which examined this scenario and several others concluded that more moderate scenarios were more appropriate.

Scenario D: The Endowment Payout Model

Here the endowment payout rate increases from the current 3.5% to 5.0%. If we had done this in 2007 the amount available from the endowment would have increased from $56.5mm to $81.4mm. But in the opinion of most financial analysts and the finance team at the University of Toronto, a 5% payout level is not sustainable in the long term and would increase the risk exposure significantly. The only way to guarantee a significant increase in the payout from the endowment is to increase the size of the endowment itself.

Scenario E: The Compensation Model

This model constrains salary and benefit costs. The impact of this would be significant because salary and benefit costs are such an important part of the cost structure of the University of Toronto. A one per cent reduction in salary increases saves $8.5 mm per year. Indeed, our analysis shows that in the long run, the impact of adjusting the starting salary is even greater than the impact of adjusting the annual increases. Starting salaries, however, are driven by market forces and the international competition for leading faculty, so there will be continued upward pressure on salary and benefits costs if we are to compete for talent. The impact of this scenario on quality would be significant as it is likely that our best people would move to other universities for higher salaries.

Scenario F: The Tuition Model

Here we project that tuition fees for out-of-province students and out-of-country students are doubled. The impact is significant to the individual student, but given the very high proportion of U of T students who are from Ontario, the impact on the financial picture of the University as a whole is minimal. When setting tuition fees for international students, we already take into account the fact that there is no Government grant supporting them; hence, they already pay higher fees. We must also take into account competitiveness with other institutions in Canada and internationally - we are all competing for the same excellent students.

Scenario G: The Research Model

In this model we assume that we receive funding for the full cost of research. For every $1 of research funding that we receive, the University spends well over ¢50 from the operating budget to support the associated indirect costs. At the present time, indirect costs are covered by research sponsoring agencies at the rate of about 16%. If this amount were increased to 40%, the immediate impact would be an increase of $60M. Again, this alone is insufficient to solve our problem.

Scenario H: The Sustainable Quality Model

This model illustrates a scenario in which high quality can be sustained over the 2030 horizon. It requires a number of variables to be altered, as shown in Tables C1 and C2 for the St. George campus. Tuition increases at 5.5% per year above inflation, instead of 2.2%. The grant increases to the national average now, and grows to keep pace with inflation. The endowment increases at 4.7% above inflation, (reaching a level of $3 billion by 2030); the payout rate on the endowment increases to 4%; other revenues increase by 0.5% above inflation; compensation is contained to 2% above inflation and student aid increases at the same rate as tuition (5.5% above inflation) to permit our continued commitment to student access as tuition rises.

The result is a student-faculty ratio of 21.1 by 2030, which is in line with a high quality student experience. The model is sustainable for the long term as all key variables are tied to inflation. Clearly there are other variations on this scenario that could also achieve a sustainable financial model for the University. The key point is that a sustainable model is possible. It will, of course, require a significant political will to implement. When similar assumptions in Table C2 are applied to UTM and UTSC, student-faculty ratios drop from their current levels to 26.2 and 24.1, respectively, as shown in Tables C3 and C4. This is a significant improvement.

Recommendations

Communicate the University’s position and value to society at large more clearly, more widely and more frequently.

There is ample evidence to support the position that a growing, dynamic economy requires an educated population to support it. More and more jobs require a post-secondary education as a precondition of employment. Parents expect and demand access to colleges and universities for their children. This is amplified by the fact that Ontario and Toronto depend heavily on immigration for prosperity and immigrants are attracted to cities with great universities. They deserve the best and we want to deliver it.

The government responds to voters, so we need to ensure that the voters understand why having a competitive set of universities is good for the province and its students.

The University of Toronto is a key driver of the economic prosperity of Ontario and Toronto – a message that should be researched, analyzed, and communicated frequently and in a variety of ways so that voters and governments understand that we are not a cost, but an investment. They need to know, and we need to tell them, what kind of return they are getting on this investment, both as individuals and as taxpayers.

All of these factors should be pushing the government to invest in post-secondary education for Ontario. There have been recent signs that suggest that the issue is understood and the provincial government is beginning to act on this understanding.

Renegotiate the relationship with the government.

The University understands the government’s position as a political body that wishes to be seen to be treating everyone fairly across the province. Their objectives are to ensure that a level of funding is provided to permit continued operation of a public system; to ensure access to post-secondary education for those who qualify; and to limit increases to the government’s budget to levels that the public will accept. We must convince them that they can achieve these objectives without controlling everything. We must convince them that they can achieve their objectives if they give up control of tuition and fees in exchange for commitments to ensure access.

As universities are publicly supported institutions and as it is assumed that the public wishes them to remain so, grants should continue to be provided on a per student basis equally across all universities. The grant should increase to the national average and the grant level should increase with inflation, at a minimum. We should begin to track and report on the Higher Education Cost Index, as is done in the US and work towards having it become the benchmark, instead of the consumer price index.

Universities should be allowed to set tuition at levels that are consistent with their individual strategies and goals. Universities should also be allowed to decide what their individual market is. U of T is likely to decide to compete on the world stage and will be influenced by a desire to attract students and faculty from around the world. We will also be influenced by the costs associated with our specific location, our infrastructure and our aspirations.

Think outside the box about relationships with donors and other partners.

Donors have been a huge part of the success of the University of Toronto and will be needed if we are to succeed in the future. Capital and endowment campaigns are attractive, but we need to find ways to convince donors to support the ongoing operation of the University. We will have to increase our tolerance for risk and accept the fact that the revenues from donors could fluctuate widely from year to year.

Corporations are willing to work with the University in a variety of ways, from funding research labs, to contracting research services, from building and operating facilities to buying training and education services from us for their own staff. We need to be creative in reaching out to potential partners and creating relationships that provide mutual benefits. We need to view corporations as our friends.

Regularly review all University policies that have an impact on the financial health of the organization to ensure that they are still relevant and achieving the desired objectives.

This will inevitably mean that assumptions will be challenged, that some cherished programs and policies may be ended, and that some members of the academy will be unhappy. But we have a long history of adaptation at the University of Toronto – a history that will help us make the changes needed for the future.

Appendix A - Mandate

The Task Force was asked to consider the issues surrounding the resources available to the University to achieve its mission, taking a perspective that was broader than just fees and grants. We were asked to review all potential sources of revenues including partnerships and ways to leverage our capital base. We also considered the use of resources to see whether there are opportunities to use them more effectively or more strategically. Resources were defined to include such things as financial resources, human resources, physical assets like land and buildings, and most importantly, the reputation of the University of Toronto, which drives all other resource growth.

The Task Force on Resources is heavily dependant on the other Task Forces to set the direction for the University. The resources of the university are strategically tied to the issues being examined by the other Task Forces and its direction will specifically flow from the priorities set by the Task Force on Enrolment and the Task Force on Institutional Organization.

Appendix B - Process

The Resources Task Force met seven times between October 31, 2007 and March 27, 2008. The Chair and Vice Chair met more often in September and October to discuss the process for the project.

A special meeting between the Chief Financial Officer and the Task Force was held to discuss endowments. The Chair and Vice Chair of the Task Force have also met with the chairs of several other task forces to determine their direction and the resulting impact on resources. The data analysis has been overseen by Safwat Zaky and Sally Garner.

The Task Force concluded early on that wide consultation was not appropriate for this topic, as even the members were hampered by limited understanding of the University financial situation. A great deal of time has been spent bringing members up to speed on the sources and uses of revenues and the various drivers that influence revenues and expenses.

The Task Force received submissions from:

- Jessica M. Barr – a letter expressing concerns about the architectural quality of recent buildings.

- Glenn Loney, Assistant Dean & Faculty Secretary, Faculty of Arts & Science on behalf of Arts and Science Council

- Ian Orchard, Vice-President and Principal, University of Toronto Mississauga on behalf of University of Toronto Mississauga.

- Joint submission from Dean Sioban Nelson (on behalf of the Faculty of Nursing), Dean David Mock (on behalf of the Faculty of Dentistry) and Dean Wayne Hindmarsh (on behalf of the Faculty of Pharmacy)

- Dean George Baird on behalf of Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design.

- Franco Vacarrino, Vice president and Principal , UTSC on behalf of UTSC

- RALUT

- The Design Review Committee

- Carole Moore, Chief Librarian – submitted on behalf of the University of Toronto Library

The Task Force focused its efforts on the discussion of how to increase revenues and decrease costs in order to support the various resources (including human resources, physical resources, social and political resources and financial resources) required by the University to conduct its research and teaching . The Task Force looked closely at the way the University is handling its resources in 2008. This information has been gathered through review of the current financial statements, budget, endowment reports and other financial documents of the University.

Appendix C

Reports

Task Force members

Geoffrey Matus - Chair

President of Mandukwe Inc.

Vice Chair of Business Board

Catherine Riggall - Vice Chair

Vice-President, Business Affairs

Varouj Aivazian

Economics Professor; Chair, UTM; Director, MFE Program

Robin Goodfellow

M.Sc. Candidate, Physical Education & Health

Scott Mabury

Chair, Department of Chemistry

Kim McLean

Chief Administrative Office, University of Toronto Scarborough

Cheryl Misak

Deputy Provost, Professor of Philosophy

David Mock

Dean, Faculty of Dentistry

Gary Mooney

President / CEO of Fidelity National Financial and University of Toronto Governor

Tom Rahilly

Trinity College, Board of Trustees

Sarita Verma

Faculty of Medicine - Vice Dean, Postgraduate Medical Education

Patrick Wong

M.D. Candidate, Medicine

Sally Garner

Senior Manager Long Range Budget Planning

Deepa Jacob - Secretary

Research and Policy Analyst for VP Business Affairs